Currently showing at the Saatchi Gallery, Newspeak: British Art Now celebrates the creative offerings of a new generation of young British artists. The collection seeks to defy the Orwellian brainchild "Newspeak" - a universal language whose vocabulary shrinks with every passing year - by showing that a multitude of visual languages are being exploited in contemporary Britain. Here are some I was drawn to:

Despite the variety on display, exhibited sound artist John Wynne highlights issues of endangerment, obsolescence and extinction. His untitled installation of 300 speakers, a player piano and a vacuum cleaner plays with these notions, as modern digital technology distributes sound through the old speakers rescued from a recycling plant. The resulting "music" is eerie - a slow-paced, perpetual, nostalgic noise pollution of sorts. In the past, Wynne has produced installations focused specifically on the subject of endangered languages, such as Hearing Voices, based on "click languages" spoken by the indigenous Khoi and San inhabitants of the Kalahari Desert.

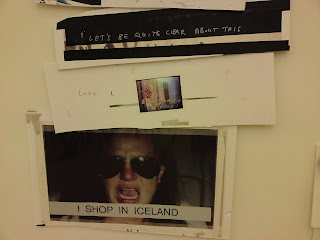

Below is detail from She Gets Even Happier, a collage crafted by the scissors and pen of Clunie Reid. By scrawling the words "I Shop in Iceland" over British Spears's face, she is mocking the cult of celebrity and the media overload that propels it. She is like Warhol-in-reverse, taking icons and making them ordinary, bringing the likes of Britney crashing down to earth from the great heights of glossy stardom.

Ged Quinn's Dreams Of Peace And Love Gradually Giving Way is based on Claude's Landscape with the Arrival of Aeneas at Pallanteum from Anglesey Abbey. The artist specialises in paintings that include contemporary images in idyllic scenes copied from classical paintings. In this particular piece, part of Aenea's ship has been recycled into a miniature cinema showing Little Tinker, and another part is carrying the Discovery from Stanley Kubrick's science fiction film 2001: A Space Odyssey.

A Joan Crawford Alphabet is typical of Donald Urquhart's work, which tends to indulge in the dark side of of Hollywood glamour in a somewhat simplistic and light-hearted way. This artwork is miles away from the 26-letter wall chart one would find in a school classroom; does Urquhart smash childhood innocence, or is he merely injecting some playfulness into his depiction of Crawford's life?